| Forum | Marketplace | Knowledge Base | | H1 site | H2 site | H3 site | |||

|

|

||

| Forum | Marketplace | Knowledge Base | | H1 site | H2 site | H3 site | |||

|

|

||

They tell you about the Hummer's 16-inch ground clearance and the 72-inch track width, its torque biasing differentials (it means you'll always have all the wheels working for you), its 6.5-liter, 170-horsepower, V-8 diesel engine, and its military pedigree as the vehicle used in Desert Storm.

The beauty of the Hummer, on the civilian road, is that it looks like nothing else. Meanwhile the other cars on Interstate 5 all look alike. Go ahead. Try to tell them apart. Chevys look like Hondas. Fords look like Toyotas. Hyundais look like Infinitis. And every sport utility vehicle appears cut from the same uninspired, sanitized-for-your-lack-of-imagination template.

The crime of aerodynamics is that it recommends conformity to one optimum shape, something resembling a vitamin pill. And then comes the boxy Hummer, which glides smoothly through nothing, paying for its uniqueness by traveling only 10 miles on one gallon of gasoline. They are charmingly inefficient.

"People ask me why do you need a Hummer?" says Dale Terwedo, a Hummer owner. "Well . . . you don't."

The $1,000-a-year in licensing fees paid by Hummer owners - new Hummers cost between $60,000 and $80,000 - go toward the infrastructure it is designed to bypass. The name Hummer is derived from Humvee, an ear-friendly term for its official military designation, HMMWV, which stands for High Mobility Multi-purpose Wheeled Vehicle. First pressed into service during the Gulf War, it was designed to be a versatile support vehicle capable of being used in any terrain.

They can do so much - able to maneuver sand, sleet, snow, mud and water - they are impractical anywhere near a city.

So naturally, they are highly attractive to Northwesterners, who romanticize the art of making life hard on themselves. We do not question the sanity of climbing rocks, bicycling up and down mountains, sleeping outside in the cold, or hiking in the rain. The only thing we love more is buying the toys that provide the means to make life difficult, thus making the said life much more enjoyable.

The Hummer, five years after Arnold Schwarzenegger became its first civilian owner, is tempting initiation into the mainstream. At Doug's Lynnwood Hummer, the newest models come to the dealership with leather seats, CD changers, power windows and air conditioning. You can get one in burgundy. AM General, the contractor that builds Hummers and other trucks for the military in South Bend, Ind., would like to see them parked in front of three-car garages. In Seattle, you might actually see two in one day. But its renegade personality still arouses curiosity.

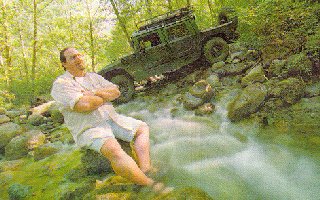

| Dale Terwedo often uses his Hummer in May Creek near Gold Bar. A car nut, he's owned 12 cars in the past four years. |

They are ultimate vehicular extensions of the Northwest spirit, what sport utility vehicles (SUVs) attempted to be. But something went wrong with the SUV. Its premise of rugged individuality became pampered conventionality. Advertised on cliffs and peaks, most of them end up in the valet lot at Cucina Cucina.

The Hummer, however stylized or savvily marketed, is a real sport utility vehicle, something you can drive without pretense while wearing your $700 Mount Everest expedition climbing jacket; your unbreakable $1,500, high-altitude, deep-sea sport watch; and your breathable, waterproof, inflatable hiking boots. DALE TERWEDO, 38, is a large man. Not a fat man, but a large man, 6-feet-5 and about 330 pounds, all of which fit comfortably into a Hummer. He is a rich man, a financial planner with almost a thousand clients who are quite happy with his work and enable him to afford a four-seat, hardtop Hummer worth about $80,000. His license plate reads "UNSTPBL," which without knowing him can come off as arrogance.

Terwedo, if he is nothing else, is self-made. His ex-Marine drill instructor father and his mother divorced when he was 6. He spent summers riding across the country in the Mayflower moving van his father drove, and winters arguing with his mother, whose only son unintentionally reminded her of her ex-husband. She, in turn, reminded her son of the resemblance.

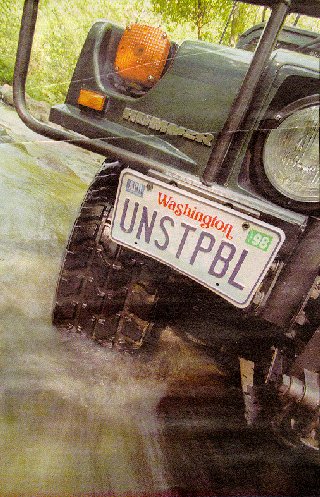

| This plate belongs to Terwedo, but may as well belong to any Hummer owner. The vehicle is not for the delicate or faint-hearted. |

At age 15, Dale left home in California and rented a room in Tacoma from his father's fifth wife. (It's not me, it's them, his father kept insisting.) Dale enrolled himself in Fife High School, made the football team and did well enough in school to earn an appointment to West Point Military Academy, all while working eight hours a day at a Shell station in the Tacoma tide-flats and painting houses in the summers.

Nowhere in Sen. Henry Jackson's letter of recommendation to West Point did it mention Dale's problem with authority. West Point did not come to pass, nor did college of any kind. He sold dictation equipment, and eventually taught himself the skills of investing money.

When he began his own business 10 years ago, he lived with his wife and two sons in a 224-square-foot trailer which often ran out of propane in the winter. This memory gives him perspective. He runs a small office in Edmonds with two employees, one of whom is his wife of 16 years, Tara. He does not spend much money on clothes or an expensive home. But he loves cars.

In addition to the Hummer, he owns a Ford Contour (for the kids to drive), and until last month at BMW sedan, which he hopes to replace with a Dodge Viper.

He is the head of the family, an agreement made between wife and husband that seems enlightened because it is so antiquated. At work, she does what he hates to do (paperwork) and he does what she hates to do (sell and glad-hand).

"It takes a good leader to be the head of a household," he said. "You can't be an ogre but you have to take charge, make decisions."

Which is the kind of thing Hummer owners seem to be good at. As a lot they tend to be confident, physically imposing, outgoing, aggressive, flamboyantly successful, geniuses. Like Tom O'Keefe, real-estate developer, now president of Tully's, the would-be challenger to Starbucks. Or renaissance man Jiang Jing Sung Baek, the cancer researcher, master swordsman, herbalist, horseman, flutist and calligrapher. He owns two Hummers, one red, one blue, one a hardtop, one a softtop. Or Nathan Myhrvold, a vice-president at Microsoft. Or Randy Johnson, one of the most intimidating pitchers in the major leagues. Alpha males. Real men.

Oops.

| Hummer salesman Steve Bell rocks a Hummer as it balances on the edge of a test pit behind the Hummer dealership in Edmonds. Bell uses the pit to demonstrate the vehicle's capabilities, often frightening inexperienced passengers. |

| The Hummer is made for extreme conditions and extreme owners. Darya, who goes by her singular name, partly submerges her Hummer in a pond near her property. She gets her speed fix in her Viper sports car. Darya is a one-woman enterprise, giving seminars to Fortune 500 CEOs at her Mossy Rock ranch. |

Darya is a woman and one of few female Hummer "pilots," as they like to call themselves. She is highly educated with a doctorate and two master's degrees. She is a philosopher, poet, and reads Russian literature. She has worked for the mayor's office in Houston, a consulting company in Washington, D.C., and been a member of various boards, blue ribbon committees, institutes and college faculties.

Recently she began her own company, REAP. Darya, 48, who goes by her singular name, gives seminars she calls "experiences," which she likens to the transformation of a caterpillar to a butterfly. In a more concrete sense, she teaches the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies to be more effective leaders. These executives pay Darya a lot of money for this information. And one of the first things they do as newly effective leaders is tell less effective CEO friends at other companies to visit Darya at the complex she has built on the site of a former 200-acre farm in Mossy Rock, two hours from Seattle between Centralia and the Cascades.

It is both her home and where she works, a complex of guest houses and meeting halls. She lives in a rebuilt farm house. She turned the barn into a studio. She bought the Hummer to transport clients around mud, fallen trees, snow and steep grades that surround the complex.

Darya, at first glance, doesn't seem to have too much in common with Dale Terwedo. She grew up in Houston, born in Mississippi at a hospital that did not treat black people. Her mother, who was passing through town in labor, negotiated an exception. She married and divorced and in the meantime had a daughter, 27, a songwriter living in Los Angeles.

But she and Terwedo both have car fetishes. In addition to the Hummer, Darya owns a Ford Explorer and a Dodge Viper, Terwedo's next dream car.

"I'm not a car tinkerer, but I love to play with cars," Darya said. "This one I wanted for work. The Viper is a toy. The Explorer is my invisible vehicle, when I don't want to be noticed."

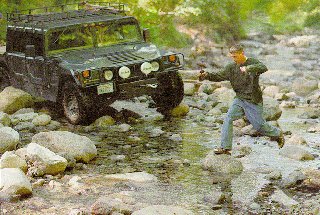

| Lending human help to a machine, Dale Terwedo's son, Ryan, helps direct his father around large rocks in May Creek. |

YOU WOULD THINK being Randy Johnson, or Jay Buhner or Norm Charlton, all of them Seattle Mariners, that drawing attention is the last thing they need. Yet they all own Hummers. It is a preemptive strike - attract so much attention with the car, no one pays attention to the driver.

"When you drive by, everyone looks at it," Charlton said. "Absolutely everyone. They don't even notice me. They're looking at the car." Charlton plans to use the Hummer on his ranch in Texas. Perfect, he said, for drives to the Gulf Coast, where his parents live.

Buhner, also a Texan, was the first Mariner to buy a Hummer. Actually his wife, Leah, bought it for him as an anniversary gift and had it delivered to the team's spring training facility in Arizona.

"I was thinking, what can I get him?" Leah said. "I mean he's got everything. I was trying to think of something totally different, which is why I decided on the Hummer.

"It fits him to a T. It's kind of this big, hard, tank kind of thing."

The spouses of Hummer owners, although they tend not to drive them, seem to understand its appeal. The wives (Darya aside) all love their husbands' Hummers, probably for the same reason they love their husbands. The kind of woman who couldn't stand having a Hummer in the driveway probably couldn't stand being married to a guy nicknamed "Bone," who shaves his head.

"I was so nervous the one time I drove it," Leah said using her best Texas colloquial manner, "my feet were sweating." HUMMER OWNERS are usually one or a combination of several things: mechanically inclined, physically inclined or mathematically inclined. The vehicle is a lesson in technology. When one or more of its wheels loses traction, full power with traction can be redistributed to the remaining wheels by deploying the brake and throttle simultaneously. Its chassis is sealed so it can drive through 2 1/2 feet of water. The tires can be deflated and reinflated with a switch on the dashboard. It can drive over an 18-inch speed bump, up a 60-percent grade and across a 40-percent bank without tipping over.

Its engineering seems to draw the interest of software geniuses. Myhrvold, Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft, drives his over the curbs at the company's campus. He's not the only one in Redmond.

Kevin Eagan, 32, is a prototype Microsoft success story. Educated at Harvard, he began at Microsoft as a college intern. He eventually became a product manager for Windows 3.0 and for interactive television. He recently became the manager of Sidewalk.com, Microsoft's online entertainment guide. The Hummer has not made him smarter or sexier but it appears to have made him a better person.

"I'm a more considerate driver," Eagan said.

And a Good Samaritan. He looks forward to snow so he can drive around pulling cars out of ditches. Several Seattle Hummer owners organized themselves into a standby volunteer corps of drivers for the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, delivering patients or vital medical supplies during snowstorms.

"I think you have to be a good person to begin with," Eagan said. "But it does unleash your creativity in a good way."

Ben Goetter, a former Microsoft employee who runs his own software consulting business, bought one of the first 300 Hummers sold to civilians in 1992. Before it, he drove a 1978 Toyota Landcruiser and before it, a 1975 Chevy Nova. He is too young, 33, to be in the midst of a midlife tank fantasy. He is 12 years new to Seattle, by way of Yale University where he earned a music degree, and Alabama, where he grew up. He has many loves: his wife Kathryn Hinsch, good wine, opera, the Thai language, the piano and his truck, which he loves "almost as much as life itself." It moved him to construct a Web site, http://www.angrygraycat.com/goetter/hummer.htm

On it he discusses automatic transmission and the masculine self-image, ARB Air Lockers versus Zexel-Torsen differentials, his Hummer's drivetrain and powertrain and its high maintenance requirements, the downside of high adventure. It comes with pictures from trips he's taken in the Hummer and modifications he plans to make to his only vehicle. Working on his truck is part financial necessity and part residue from the same hormones that compelled him to take high-school shop class.

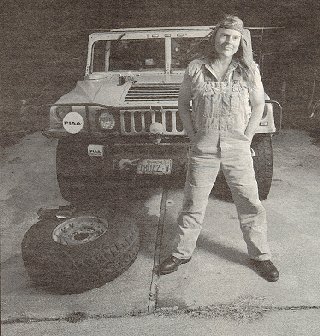

"My truck currently has enough scars, dents, and poorly repainted patches to pass for a military surplus model," Goetter wrote on his Web site. "I like it that way."

With long hair held by a bandana (a look that suggests Mad Max), Goetter does not speak, live nor drive delicately - a terrifying image for the folks he calls "crunchies," many of whom are his neighbors in Wallingford. So how to reconcile nature and the Hummer, a vehicle specifically designed to conquer it?

Hummer dealerships promote membership in "Tread Lightly," a club designed to educate offroad-vehicle drivers on ways to have fun without harming the wilderness. It is a good public relations tool as much as anything, a token to appease environmentalists, who probably don't have to worry much about Hummer owners if they are like Goetter.

He has never tread upon meadow grass or forest fern. In fact he drives only on roads. Very bad roads, but roads nonetheless.

"The term offroad vehicle is a misnomer," Goetter said. "It reminds me of firearms ownership (he is a target shooter). With power comes responsibility and you have to answer that responsibility."

DRIVING OVER Snoqualmie Pass during a particularly fierce winter storm, Tom O'Keefe slowed to greet a state trooper, who was instructing drivers to turn around and go back to the city. But he thought O'Keefe's Hummer was a military vehicle so he waved him through. The trooper figured it out when he saw the "Tully's Coffee" sign painted on the side of the Hummer, but not before it was halfway to Yakima.

O'Keefe, 43, is a former real-estate developer who started Tully's, sometimes to the annoyance of Starbucks president Howard Schultz. O'Keefe's approach is shrewd if not subtle. He lets Starbucks open a store first and establish the foot traffic, then opens a Tully's store a few doors away.

"It's like a power dive, fake to the fullback," O'Keefe said. "And we're the nimble tailback behind him."

Tully's recently moved into Starbucks' old headquarters near Boeing Field and uses the company's former roasting plant. Moreover, O'Keefe works in Schultz' old office. Both coffee moguls were mentored in large part by real- estate developer Jack Benaroya. Although their lives converged into coffee, they remain divided by the Hummer. Schultz drives a Jaguar.

O'Keefe, the son of a chemistry and physics professor, moved to Issaquah from western Massachusetts during high school, when his father was hired by Boeing to work on the SST. Like Schultz, O'Keefe grew up in a culture of sports. O'Keefe's father coached football, basketball and baseball in high school. O'Keefe played all three sports.

More a businessman than a coffee guru, he claims to have had toast and coffee for breakfast since age 3.

"Two sugars and cream," he swore.

He decided to start Tully's after he noticed how many storefronts he was leasing to Starbucks.

O'Keefe was driving home late one night on Dearborn when he took a corner wide and nearly sent this certain Jaguar into another lane "purely by accident." He quickly recognized the startled driver of the Jaguar, with whom he is, despite being a rival, on friendly terms.

"I started laughing," O'Keefe said. "First of all I didn't expect to see a car, then when I saw who was driving . . ."

| On his web site, Ben Goetter says his truck "currently has enough scars, dents, and poorly repainted patches to pass for a military surplus model. I like it that way." |

Since he has been selling them for four years, a few have been traded in, making it possible for some slightly less wealthy customers to buy a used $35,000 Hummer.

Kyle Duncan is a tooling inspector for Boeing. He is a former auto mechanic who earned two associate degrees in civil and mechanical engineering. He makes a good living at Boeing, but he is hardly rich. He traded in a tricked out 1987 Chevy Blazer for his Hummer, which had 60,000 miles on it and needed a lot of work. He worked on it himself to save money.

He uses it for camping and fishing trips. He is more or less an average guy, except for the Hummer. Perhaps he is a sign of things to come, average Northwest guys who drive assault vehicles.

"For the amount of Hummers sold around here, you very rarely see them on the road," Duncan said.

"I am making a pretty good living, but I'm making a pretty good car payment, too."

Hugo Kugiya is a writer for Pacific Magazine.